With a virtuoso display of finishing in Salvador, the Dutch chastened a Spanish side indelibly influenced by their own footballing past – and by their current manager Although it is tempting to view any successful team, particularly any international team, as causa sui – as a product of its own footballing culture and nothing else – the reality is that successful teams have always looked abroad for inspiration. Perhaps, in part, this is simply down to the natural allure and exoticism of that which is foreign. Just as the hosting of this World Cup in Brazil possesses a romantic appeal arguably unmatched by any country closer to home; perhaps even England itself; it is worth remembering, conversely, how top Brazilian sides such as Corinthians, Arsenal and Sao Paulo Athletic Club self-consciously retain their original English monikers, in testament to their English origins.

Indeed, for all that Brazil’s playing style can be considered originally and organically Brazilian, the individual dribbling so characteristic of jogo bonito was a distinctly English tactic when football was famously established in Brazil by nimble winger-cum-railwayman Charles Miller, a well-to-do Englishman of Scottish descent who took it upon himself to act as a sort of footballing missionary across the South Atlantic. The game Miller preached was based first-and-foremost on individual dribbling; dribbling he had honed on the pitches of the public schools that, unsurprisingly, valued the assertion of individuality above just about all else. Even that most revered and romanticized of footballing styles, therefore, can be said to ultimately originate not on the sandy beaches or narrow streets of Brazil itself, as might be imagined, but under the drizzly skies of nineteenth-century public-school England, some six thousand miles away.

By the very same token, the responsibility Spain possesses for tiki taka, the possession-based style so imperiously successful prior to the interventions of Arjen Robben, Robin Van Persie and co. yesterday, doesn’t lie solely with the Spanish. The twist here, however – a twist of which Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein, would be proud – is that the team who so emphatically ended Spain’s tiki taka reign yesterday represent the very nation who can claim to be the forerunners of tiki taka itself. For just as, in Shelley’s gothic novel, Victor Frankenstein eventually manages to destroy the immensely powerful monster which he, many years before, had created; so Holland destroyed a Spain team yesterday whose very blueprint for such immense prior success as winning every tournament since 2008 – tiki taka – has historically been developed by the glow of Dutch, and not Spanish, candlelight.

The early phase of tiki taka’s development belongs to a name familiar to football fans everywhere: Johan Cruyff, inspiration, ideologue and all-round icon of Dutch football, if not world football, in the 1970s. At Ajax, Cruyff acted as the keystone of a side who bewitched European audiences with a brand of football based around one essential – namely, the ball itself. More precisely, both the retention of and the regaining of the ball were upheld as sacrosanct, with Cruyff, at the prerogative of his manager Rinus Michels, actively enforcing these dual principles on the pitch. However, to the extent that this can truly be gauged, it is fair to say that the principles were really Cruyff’s, and not Michels’s, or at least became Cruyff’s. The lengths to which Cruyff cajoled and criticized team-mates for ball-related mistakes simply seems too great to fall within the scope of mere subservience to managerial prerogative.

For Cruyff, football based on retaining and regaining possession wasn’t simply preferable in aesthetic terms. It was, more importantly, the most efficient way to play football; to fail at either was, therefore, to do nothing less than harm your team’s chances of the best possible result. Famously, Cruyff once even criticized his Ajax team mates for scoring a goal, arguing it should have been scored earlier in the play. To criticize a misplaced pass is one thing, but to criticize a goal for its perceived inefficiency suggests a genuine personal belief on Cruyff’s part that Michels’s footballing principles were right. What kind of manager, after all, would actually encourage his or her captain to criticize goals? Not Michels. No, the one who truly enshrined in footballing scripture the principles of retaining and regaining the ball was Cruyff himself. Scripture which, as his indefatigable personality might suggest, he was prepared to preach as far and wide as possible.

Hence, when Cruyff eventually retired from playing in 1984, ending a dazzling career which contrived merely to harden his footballing principles, coaching and instilling these principles seemed the only realistic option. Deeply influenced by his spells at Ajax, and later FC Barcelona, Cruyff proposed that a copy of Ajax’s academy (of which he and many of his 1970s teammates were highly successful products) be set up at Barcelona, a proposal gamely accepted by then-club president Josep Lluis Nunez. The result was La Masia, or ‘The Farmhouse’, a proving ground nestled amongst traditional Catalan idyll, but which practised very Dutch, and very demanding, training methods. That being said, winning among younger age groups was never prized, with younger Barcelona age-group teams frequently losing to equivalent sides from smaller clubs. All the value lay in the ball, as Cruyff would have it, training sessions peppered with constant games of rondo, or ‘keep ball’ (indeed, the very name ‘tiki taka’is said to simply derive from the sound the ball makes when passed first-time between teammates). Losing the ball, as well as failure to regain it quickly enough, were the true losses.

Amongst the first crop of youngsters to graduate from La Masia was one Pep Guardiola, who emerged when Cruyff himself was Barcelona manager. Indeed, were it not for Cruyff’s direct intervention during Guardiola’s very first week at La Masia aged 13, Guardiola would never have become the pass-master so pivotal (both metaphorically and positionally) to Barcelona’s style in the ‘90s, and to their astonishing later success under his management. Cruyff explicitly requested during a youth team game that youth team coach Charly Rexach switch Guardiola from the right of midfield to a ‘pivot’ role in the centre, from which he could best utilize his obvious awareness and technique; a role which Guardiola never left at Barca until 2001, some 17 years later. Naturally, with Guardiola having helped secure Barca 16 trophies during his career and with his star beginning to wane, the Barcelona manager at the turn of the century actively nurtured a successor: the great Xavi Hernandez, arguably the single most important player behind Spain’s recent dominance, and the player most emblematic of their tiki taka style.

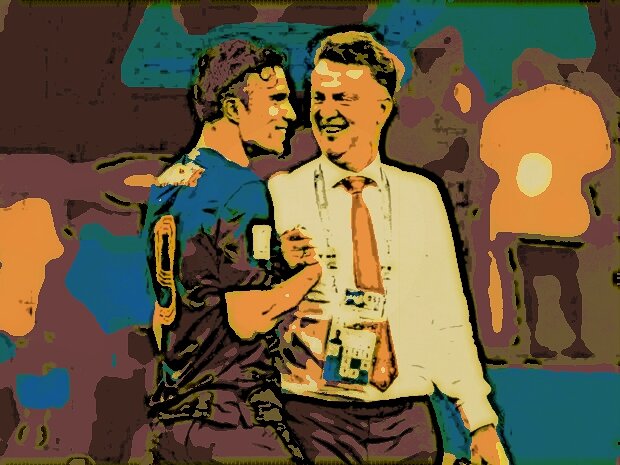

So who was the Barcelona manager at the time? Answer: none other than Louis Van Gaal, the very same Dutchman (minus the receding hairline) who oversaw Spain’s humbling yesterday in Salvador. Louis Van Gaal, the man who also brought Andres Iniesta from La Masia to the Barca first team and onto World Cup-winning superstardom with La Roja. Louis Van Gaal, the man who yesterday conspired to kill off – possibly for good – the footballing behemoth which he and his fellow Dutchmen have largely served to create. Louis Van Gaal – the man who yesterday imbued a football match with a Shelley-esque literary resonance the likes of which we may never see again.

CW, 14/6/14

Comments 20

A few thoughts:

As an added twist, van Gaal defeated the ideology he helped to refine through a partial antithesis, direct attacks based around pace in a two striker set up. Yet the team that defeated them had much of tiki-taka about them (a back 3, which Holland and Barcelona morph into) technical proficiency, positional intelligence+a high line). So in many senses van Gaal represented an antithesis, but an antithesis refined by the tiki-taka which he initiated in its’ current form. Which is just another form of circularity (in a very loose sense of the word).

Another note of interest on Iniesta is the failure of him to break through in his original position, which was as a highly defensive regista. Only when he was moved forward by Rijikaard did he really break through.

Also worth noting just how intense the dutch pressing was for its’ time, the cherishing of the ball was such that it needed to be repossessed as quickly as possible. It led to defending where 5 players with charge the player with the ball, quite literally. Unfortunately, it may have been caused by drugs, Dutch team doctor was notorious in other sports for use of pills that ‘made you feel like Iron’.

Holistically though, wonderful article.

Author

Cheers for the comment, I had no idea that the Ajax of the 70s were (allegedly) on drugs! Good to know there aren’t similar rumours surrounding Spain 2008-2014, or indeed Barcelona under Van Gaal or Guardiola. At least it can be said that the pressing/regaining-of-possession approach isn’t drug-dependent – drugs only control the speed at which players can press, and not the will or ability to press itself.

Wholly agree that Van Gaal’s Dutch team were reminiscent of ‘tiki taka’ in many ways as you say; it’s a point I wish I’d made in hindsight. It’s as if Van Gaal knew tiki taka (or, at least, its Cruyffian origins) so well that he ended up being tiki taka’s worst enemy in the end. He distilled a superior method from the original tiki taka, if you like, ultimately to the detriment of the original formula.

As for Iniesta, well……… Rijikaard’s nationality can probably be guessed! But, yeah, it’s true, Van Gaal himself can’t take all the credit for Iniesta’s emergence.

The doctor was called John Rollink. Perhaps a terminological distinction, but I would also argue that it was influenced by tiki-taka (in that it was profoundly shaped to exploit weaknesses, with exactly the same kind of qualities technically) than reminiscent. That is what linguistic ambiguity does, unfortunately (I know you agree, I just want to make it explicit, for fun!).

Well-written article. I applaud you. However I don’t fully agree with you on the Dutch roots of tiki-taka, though. As both a Dutch person and an Atlético Madrid, I might have a different take on this. “The Dutch School” and “tiki-taka” are two separate things. The Dutch School is, roughly, about evenly distributing players around the pitch and creating patterns of movement characterised by players switching position by to lure defenders out of position which creates space for other players to move in. Even distribution, fluidity and pressing are central, possession is not. The Dutch School has had a huge impact on the Barcelona youth system and coaches like Cruyff and van Gaal have had lasting impressions on players like Guardiola and Xavi.

The birth place of tiki-taka, is not la Masia, however. It is Las Rozas, a sleepy suburb of Madrid. Here Luis Aragonés summoned Xavi into his hotel room, sometime in 2005. In an expletive-laden conversation (as per usual with Aragonés) Aragonés laid down his plans for the national team, and Xavi in particular. Xavi had been terrified he would be left out of the selection, because his own was not great. Despite Barcelona playing an interesting mix of ‘Dutch School’ and Sacchi-isms under Frank Rijkaard. After talking to Xavi, Aragonés got all the “little ones” together (Fabregas, Silva, Cazorla, Villa, Iniesta) and started to drill them into a possession-based machine. The ‘tiki-taka’ experiment was already going on for 3 years (and had won the European Cup) before it came to Barcelona when Pep got promoted to manage the first squad found a way to blend the ‘Dutch School’ with the tiki-taka qualities of his players and created the title-winning juggernaut that was the Pep team.

Still, I agree with you. The problem in Salvador was tiki-taka. It has died in the same year as Aragonés did. The main problem that match is that tiki-taka, with its pass-heavy focus on possession, has the tendency to make a formation “collapse in on itself” and it doesn’t spread out evenly as the ‘Dutch School’ proscribes. Van Gaal’s 3-5-2 exploited the lack of width and Spain were Blind-sided. Morale: you can use a tactic you learn from your master, but if you fail to execute it perfectly, he will know exactly how to exploit your flaws.

Author

Hi Wouter, thanks for taking the time to comment, especially in so much detail, I appreciate it. Yeah, I admit that my article does take a more broad-brush approach to the origins of tiki-taka, and may not be 100% accurate regarding its origins, so in many ways thanks for correcting me. Saying that, I wanted to keep the article length down to not much more than 1000 words, for the sake of being concise, but also simply because of time constraints. To go into the history behind it all could fall within the scope of an entire book, and being a uni student I just don’t have the time to cover every aspect of it, as interesting as that might be.

To address your main point, the ‘Dutch school’ of positional interchanging, and emphasis on utilizing space, is something I was aware of. The article was really more of an attempt to acknowledge the influence on Spain’s team of several individuals who all happen to be Dutch (Cruyff primarily, but also Michels, Van Gaal, Rijikaard, as well as the Dutch team that actually beat Spain in Salvador) rather than any general Dutch school (I don’t mention totaalvoetbal at any point for this very reason). Certainly, as far as I can see, Cruyff and Michels in particular revered possession of the ball, and concerted attempts to win it back quickly, for all that positional interchange was undeniably a part of the Ajax ’70s team. Guardiola’s fully establishing tiki taka is also, I think, inconceivable without acknowledging Cruyff the individual’s influence , even if ‘tiki taka’ and the ‘Dutch school’ of which Cruyff was a part are distinct entities.

Regarding Aragones and his training drills with Xavi et al, that is simply something I didn’t know and never found out when researching this, so all I can say is thank you for adding to the story! Given tiki taka’s (arguable) emergence on the international stage was when Aragones was manager in 2008, the fact he was practicing possession-orientated drills with the ‘little ones’ is unsurprising, but interesting to hear nonetheless.

Overall, though, the article does not purport to tell the whole story of tiki taka; it is more a deliberately selective attempt to highlight the strange Frankenstein-esque circularity of Holland’s victory. In that sense, it is more a light-hearted article than a serious history, although once one acknowledges its deliberate selectivity, I would say it still possesses fair historical merit.

Anyway, thanks again for the comment, you taught me something I had no idea about regarding Xavi’s self-doubt and concerns with Aragones (not surprised about Argagones’s expletives, as you say!). Just to add, the site in general is still in its infancy, but should be fully set up by early September. Cheers! Charlie

Cool, will be looking forward to that. Great to have a website where thought and energy are put into that are posted

Most of the Xavi/Aragonés story came out after Aragonés passed away. Xavi even wrote a column himself talking about their special relationship, which was published in a Spanish newspaper, I think it was el Pais.

Thanks for that info, v. interesting. Unfortunately, I don’t speak Spanish. Do you know of any translation?

Author

I speak some (limited) Spanish, was compulsory during school until 16, could have a look when back in St Andrews?

The orginal:

http://deportes.elpais.com/deportes/2014/02/01/actualidad/1391284340_205577.html

Some parts are translated here:

http://www.insidespanishfootball.com/96741/xavi-7hernandez-pens-open-letter-to-the-late-luis-aragones/

Oh, and I’m fairly certain Rexach is Catalan

Author

Yes, this is true, will alter that now. My mistake, thought Rexach was Dutch. Can see now why he’s Catalan though, the ‘x’ in his name that gives it away (Txiki Begiristain, the Man. City, former Barca director of football, could only be Catalan with a name like that!!). Cheers.

Hi Wouter, thanks for the (highly intelligible and provocative, lots I was not fully aware of) comment. Since I am not the author, and have (relatively) little knowledge on this particular area, I will leave the author to comment in a more detailed way. However, I offer a few thoughts.

a) I agree on the dutch school being fundamentally based around even distribution of space and pressing. Are you saying that possession was a mere byproduct of this (a la Potchettino Southampton)? Would be interesting and quite possibly correct, I am no expert on dutch football. On positionally interchange, this is certainly true (esp. with Blankenberg+Neeskens). Though tiki-taka concerns itself with this, especially when Keita was in the team, funnily enough, that was when Barcelona hit their most fluid. Though I would in general agree that Barcelona were based less (and engaged in far less interchange), and put far more emphasis on central spaces and using flanks as a defensive tool.

b): Would you say that tiki-taka was played for four years prior to Guardiola? By Rjikaard? Aragones I will accept, emphasis on possession and centrality. But my memory (incredibly faded) of that Barcelona team was massive individualism and more conservative, less positionally ambitious and fluid midfield, which was not direct, but more direct (certainly in the CL . Though there was certainly an emphasis on possession.

c) Euro 2008 is interesting in terms of tiki-taka. It certainly could have claims to be initiated (Barcelona the season before had elements). But the press talked of the screen in Marcos Senna, it had two orthodox forwards (until Russia, when it began to succeed) and scored regularly through direct attacks. No better example than the final. Could even argue it was an fluky piece of luck that created one forward tiki-taka which allowed for greater width, which in turn created more central space. Again, my memory isn’t the best of this tournament (I am substantially younger than you, I am presuming). Still, I pretty much agree with you in general here.

d): This would be my substantial disagreement with you. I agree wholly (and wish it was emphasised more) in the first part. Tiki Taka does create a formation that collapses on itself (see the total suppression of space the formation creates for forwards, it also creates clear and obvious ways in which you can attack it (direct balls behind wing backs who are required to give it width. Best example of this I can think of would be Chelsea vs Barcelona, balls behind Alves to Ramires. But I would argue that what killed Spain in that match was having two centre forwards who can interchangeably run in behind, against a high line with a player capable of hitting long balls accurately from relatively wide or deep areas (Blind). Always feel that Spain were vulnerable 2 vs 2, Ramos and Pique are not great without cover.

Again, thanks for the comprehensive and highly provocative comment, lots raised I haven’t addressed, I agree with a good 90% of what you have said, some of it I don’t feel informed enough to comment on.

Would also be interested to know the Sacchian elements of Rjikaard, would seem likely, but I am very interested to hear them explicated.

Normally I can’t stand BleacherReport, but you might be interested in this, Oliver. It gives an overview of Sacchi’s playing style: http://bleacherreport.com/articles/1425160-great-team-tactics-breaking-down-how-arrigo-sacchis-ac-milan-took-down-europe

Sigmund,

Was broadly aware of the contents of that BR article (though was pretty good for a BR article, some can be awful), I really need to sit down and watch some games of that team. Theoretically it was all about controlled press, incredibly compressed game, offside trap, equal utilisation of space, and total universalism (what better a symbol that Ruud Gullit, striker, central midfielder and sweeper).

Thanks anyway,

Oliver.

A bigger focus on the physical side and not just stamina and grit, but also strength and height. A preference for strong, tall full backs (the likes of Belletti, Abidal) and centre mids (Edmilson, Toure). Themidfield was quite tenacious as a whole (not that weird with Neeskens as his assistant), with van Bommel and Deco also known to get stuck in at times. Xavi once said Rijkaard made him feel like an unfit part of the bigger Barcelona, “like a cancer”.

Thanks, inferentially appears about right. Midfield in particular appears aboutt right, interesting about Neeskens influence. More diagonal balls too, with Marquez?

One final thing.

I guess it depends on what we are denoting tiki-taka to be. Are we talking of the later Spanish, ultra-conservative ball hoarding, width denying tiki-taka of 2009-2012 Spain. Or are we talking of the (more dutch?) conception of tiki-taka as an integrated pressing system, with more directness (because they had the individual brilliance of Messi to retain the ball while being so direct)+ highly width dependent (and possible because of superhuman Alves), far more positional interchange.

You hit the hammer on the head there. For me, tiki-taka, as it was developed in the Spain squad, is a defensive tactic first and foremost. Get hold of the ball and under no circumstance lose it, so the opposition can’t score. Beneficial side effect is that opposition will tire from running after the ball, start losing concentration and make little mistakes, which creates space for you to exploit. It’s very dull to watch on its own (“boring Spain”).

The power of Guardiola was that he adopted the tiki-taka defensive method and combined with Barcelona’s own Catalano-Dutch hybrid of playing wide and pressing.

Back to that fateful night in Salvador (disclaimer, my perceptions might be very much wrong because of the shenanigans that ensued after the final whistle). My view of it is that Spain made a hash of it because they tried to play like Barcelona (including the pressing), but forgot to mimic their shape. Because Spain played so narrow, there was no pressure on the back three to stretch out. The back three were sitting back quite comfortably (although de Vrij was struggling with Costa runs behind his back, but that has nothing to do with tiki-taka). This gave the Dutch wing backs license to roam forward. Because Spain tried to press up, this left the Dutch wing-backs 1-on-1 with Alba and Azpilicueta and Ramos and Pique were left to deal with Robben and van Persie. Both Azpi and Ramos were quite clearly out of their depth during Dutch counter-attacks.

Spain clearly had a better players and should have won easily had they ensured the right amount of width, Sure, Navas was out with an injury, but not taking a like-for-like replacement to the World Cup was a mistake. A second option was starting Atlético Madrid’s Juanfran as right back. A converted winger, he knows how to make Alves-like runs and get to the byline.

Ya, I said at the time that they should have had Fabregas in as a False 9 (to create a 3 vs 0 situation), Pedro/Navas stretching play, perhaps moved to 4-3-3 to have Busquets dropping in to cover. Azpilicueta was a also a mistake, being a Chelsea fan, he is unwilling to move high enough up the pitch to get the ball, leaving Blind relatively free. Understandable why, given Van Persie can make a run wide of the RCB.

Was Juanfran not omitted for fitness reasons?